Lionel Morgan was born on the Tweed on August 12th, 1938, the third of four sons to parents with Ni-Vanuatu ancestry. As a boy, he was very polite and respectful. He listened carefully to what his parents taught him about life and was very well thought of by his teachers. As part of the Tweed ‘black’ community, there was no segregation of tribes or nationalities. Whether you were a mainland Aborigine or South Sea Islander, the community leaders instilled a culture of inclusiveness. As far as integration with white people went, it was up to the individual. No barriers were put up by the elders. If you wanted to mix you did, and if you didn’t, you didn’t. You weren’t compelled either way. Lionel decided from an early age that he would be ‘colour-blind’ and just treat everyone the same.

As a student at Tweed Heads State School he was quickly recognised as an elite athlete and was chosen to represent his school at rugby league. However, his career almost came to an end before it even started. When he was about 13, some students were fooling around on the school bus and Lionel got pushed out the door. As he landed, he fell under a wheel and the bus ran over his right knee. Fortunately, it had been raining for two weeks and the ground was soggy, so when the bus wheel went over his leg the ground gave way to some degree. When the doctors examined him, they thought that he would be flat out walking, let alone playing sport again. However, after having an operation and undergoing some rehabilitation, he found that, fortunately, he hadn’t lost any pace.

The highlight of his schoolboy sporting achievements was being chosen to play in the NSW Primary Schools competition in 1952 as a member of the country side. They were billeted out in Sydney and Lionel stayed at Arncliffe with Kenny Anderson, who ended up playing for Brisbane Norths and was a Bulimba Cup representative. Reg Gasnier was two doors down from where Lionel was staying and they got to know each other to the point where when Lionel made the Queensland side, Reg came looking for him to catch up. Lionel played two games at the carnival and it was there that he first showed his goal-kicking prowess on a major stage. His team had just scored a try near the end of the game and were one point behind. The coach asked Lionel if he could kick, and Lionel said that he could. Kicking barefoot, he lined it up from the sideline and it went straight through the middle of the uprights, giving his team the win. He played well enough at the carnival to have observers saying that he was a young player with a bright future.

In 1955, Lionel joined the Tweed Seagulls and played for the Under-18s at centre. Despite the fact that he was only 16 years of age, he was made captain and stayed with the team for two years. Barry Muir, who would go on to play 22 Tests for Australia, was the team’s half-back. Tweed Seagulls was established in 1908 and has the distinction of being Australia’s oldest provincial rugby league club. After his time at the Seagulls, Lionel decided to play for the famous Tweed All Blacks, although his mother, being an ardent Seagulls supporter, wanted him to stay where he was.

Founded in 1930 when the local clubs refused to let ‘blacks’ play in their teams, the Tweed All Blacks had built a sterling reputation for exciting play, based on speed and agility. The 1930s team was considered the best club team on the North Coast at the time and included standout players such as ‘Stoker’ Currie and Walter Slockie. Arthur ‘Stoker’ Currie (the grandfather of Tony Currie) played for NSW Country in 1937 in bare feet. In 1938, the All Blacks played a Brisbane City reserve team, winning 29 to 8, with Stoker playing a splendid game. Walter Slockie played a season for St George in 1925 on the wing, scoring five tries. Approximately 10 years later, he helped to organise regular exhibition games for the All Blacks in Sydney against his old club. Wins against St George had a significant flow-on effect. They so inspired the Sydney Indigenous community that the Redfern All Blacks were formed. Nathan Merritt and three previous generations of his family played for the Redfern team, as did two of Greg Inglis’ uncles.

In 1957, when Lionel joined the Tweed All Blacks, many ex-players from the 1930s had mentoring or coaching roles. ‘Uncle Stoker’ was one of Lionel’s main mentors and Walter Slockie, being an ex-winger, gave Lionel lots of tips about playing in this position after he moved from full-back to the wing. Reggie Booker, the 1930s’ team goal-kicker, nurtured Lionel’s considerable goal-kicking talents. These men helped Lionel and the other players with their football, but also by guiding them to become productive members of the Tweed community. With Lionel, they would spend hours talking to him. They helped him to develop the mental fortitude to not get angry about racist things – having the maturity to handle himself well and not get sucked into retaliation. They also encouraged him not to drink or smoke. He never did and it never worried him that he didn’t. Lionel had a saying, ‘Don’t make the publicans or the tobacconists rich’.

In 1958, the All Blacks had a banner year. In June, the won the Anthony Shield and in September they became the Tweed Competition premiers. At the end of season carnival, held in Murwillumbah, there were athletic events. Each team would put up their fastest runner for a sprint race and Lionel was chosen to represent the All Blacks – and won. Bill Castner, a butcher from Wynnum Manly and a ‘scout’ for his local club, was at the carnival to see Lionel. He spent his holidays each year fishing at Tweed Heads and in the two previous years he had asked Lionel to come to Queensland to play for Wynnum Manly. But Lionel’s parents said he was too young. Finally, in 1958, they agreed to let him go.

Lionel told his friends about his ambition to go and play in Brisbane. He also said that he wanted them to come and watch him when he represented Australia. They thought it was a huge joke and told him he would only last a couple of weeks in Brisbane and then he would be home again. Lionel was not arrogant – he just had an amazing belief in himself and his ability to play well. Although he didn’t know exactly where Wynnum Manly was, he had the self-confidence to be successful. In 1959, when Lionel started playing for his new club, his mother and Tweed Heads supporters would hire a bus to go up and watch him in action. Later, when he played in his first Test match, 20 busloads of supporters from the Tweed, including the friends that had doubted him, came to see him play.

As the All Blacks had disbanded at the end of the 1958 season, Billy McDermott also decided to come to play in the Brisbane competition. He had played at centre in the NSW Schoolboys competition on the same team as Lionel and they had become good friends, although Lionel was older. Billy was all set to go to Brisbane Easts, but Lionel had a word to the Wynnum Manly officials about the centre’s playing ability and suggested that they talk to Billy about coming to Wynnum Manly instead. They weren’t disappointed, with Billy becoming one of the club’s best players and going on to represent Queensland.

When Lionel played his first few games in the 1959 season, Wynnum Manly supporters soon discovered that their new winger was an outstanding acquisition. Lionel was an electrifying runner, with amazing acceleration. But the thing that really made him stand out was his elusiveness – he had arguably the best right-foot step of his era. His forte was to run within a metre of an opposition player and in the process bring him across and then step back inside him as the opponent was coming flat out and leave him flat-footed. Lionel demonstrated just what he could do in his first club game at Lang Park. The Wynnum half-back at the time, Neddy Green, said to Lionel before the game, ‘I heard you are pretty fast. We’re going to see how fast you are today’. When Wynnum won a scrum 25 yards out from their own line, Green ran around to Lionel’s wing, shouted ‘Here, see how fast you are’ and passed him the ball. Lionel sprinted away and scored under the posts. When Lionel came back for the kick-off, smiling, Neddy had to concede that, yes, Lionel was fast.

At the time that Lionel joined Wynnum there were very few ‘black’ players in the Brisbane competition. However, diehard Wynnum supporters did not care about the colour of Lionel’s skin, despite the papers invariably adding the words ‘coloured winger’ whenever referring to him. Lionel was very happy with the support he got from his home crowd, on and off the field. People on the street would stop him to say hello and wish him all the best, or ask for an autograph. Lionel and some of the other players would sell raffle tickets at several different spots in the Wynnum Manly area, spending about an hour in each place. Local fans were happy to buy tickets from any of the players, including Lionel, in order to support their local team, and the players would give that support back on match day.

The club was just as supportive. As soon as he arrived, the Greenhall brothers took him aside and let him know they had his back. They looked after all the backs in the backline – to ensure opposing players left them alone. ‘You score the tries, we’ll do the hard work for you.’ The brothers were two of the toughest men playing in the Brisbane competition. When you were tackled by them, you certainly knew it. The rest of Lionel’s teammates were only concerned with how well he played and how he could help them win more games. The Wynnum Manly club was one of the few in Queensland to openly embrace Indigenous culture and players. One of their life members, by the name of Glen Alfred ‘Paddy’ Crouch, played junior football for the club and played for Brisbane and Queensland. Also, when Wynnum Manly built a new ground in the 1960s, it was named Kougari Oval. The word kougari means ‘seagull’ in the Yugumbir tri’ language, a tribe from the Logan and the Albert River areas.

As a boy, the player that Lionel most looked up to was Clive Churchill. He liked his playing style, and the schoolteacher that tutored Lionel in rugby league, by the name of Tom Peate, was also a Churchill fan. Lionel had the opportunity to go the ’Gabba to watch him play in 1956 and wasn’t disappointed. When Lionel came up to Brisbane in 1959 he had the opportunity to meet his boyhood hero. Brisbane were to play a game on Easter with Central Queensland in Rockhampton, and when several of the first-choice Brisbane wingers pulled out, Lionel was asked if he wanted to go. The team journeyed up by train and Lionel had a chance to have a chat with his coach – Clive Churchill.

Lionel discussed with Clive the way he wanted to play. Rather than be a traditional winger that stayed on his side of the field, Lionel wanted the latitude to roam, looking for opportunities to insert himself into plays at opportune moments. He felt he could be more effective that way. Clive’s reply was that when the team was in attack Lionel could be anywhere on the field that he liked. He had speed and deception, so that was fine. However, when the team was defending, he had to be back in position. If he wasn’t, the opposition wingers would be too dangerous. Lionel thanked Clive for the support and agreed to be ready in defence. Every coach that Lionel had after this basically had the same idea – roam wherever you want in attack, but get back into position on defence.

Two weeks later, Lionel was chosen to represent Brisbane in the first Bulimba Cup game of 1959. He had an impressive debut, scoring three tries and judged the best player on the field. Brisbane easily won the game against Toowoomba, 34 to 10. The second game, on April 18th in Brisbane, was a bigger challenge – playing Ipswich, the defending Bulimba Cup champions – but Brisbane came away with a comprehensive 34 to 13 victory. This time Lionel scored two three-pointers. For the first try, Brisbane centre Geoff Little passed him the ball just before the halfway line. Lionel side-stepped around his opposite number, Brian Walsh, and then after beating the full-back, raced downfield to score under the posts. His second try also came about when sidestepping his opponent. Both were scored from a distance of 60 to 70 yards. ‘Uncle Stoker’ had come to watch the match and support the Tweed youngster. When talking to journalist and ex-Queensland captain Jack Reardon after the game, and with Lionel standing nearby, he said that, ‘We have just seen the first Indigenous player that is going to represent Australia’.

Games against Ipswich did not always go so easily, especially when visiting teams played them in Ipswich. Many players felt that the Ipswich fans were the most passionate, especially when a ‘wrong’ had been done to one of their players. On one occasion, Brisbane were playing Ipswich at the North Ipswich Reserve when Barry Muir flattened Booval Swifts’ second-rower Jimmy Foreman. Shortly afterwards the Brisbane trainer motioned to Lionel, who was closest to the touchline and said not to worry about shaking hands at the end of the game and to run straight to the dressing room. When Lionel asked why, the trainer pointed out a section of the crowd that looked decidedly angry. Lionel relayed the message to Barry, the Brisbane captain. Barry also asked why they needed to leave so hastily, and Lionel just said that was the message. Barry realised what was going on, marshalled his troops at full-time, and they quickly ran to their dressing room. The team had to wait for at least 45 minutes for the angry crowd that quickly gathered to dissipate before they could leave safely.

A week after his second Bulimba Cup game, there was some controversy at Kitchener Park, Wynnum Manly’s home ground. Due to injuries, Lionel was chosen to play at centre for a game against Valleys. When told about the decision, Lionel was happy to agree as he had played centre before when on the Tweed. The club issued a statement saying that Lionel was a good team-man who was helping his club when they were in a tight spot, but many supporters were angry about the selection, not wanting to see their high-impact winger shifted to a position on the field where his talents might not be fully shown. They needn’t have worried. After the match, Clive Churchill commented positively on Lionel’s impact on the game, and his Brisbane career to that point. Churchill praised Lionel for his ability to continuously score tries with runs of 50 to 70 yards. His exciting play helped to bring in the crowds, as evidenced by the fact that the game drew around 7000 spectators. He had become one of the most entertaining footballers in the Brisbane competition.

The game against Valleys was the first time Lionel would come up against popular Valleys full-back and goal-kicker Norm Pope. Pope had captained Valleys to premierships in 1955 and 1957 and had kicked 86 goals for Brisbane in Bulimba Cup competitions between 1950 and 1958. Although he was no longer playing representative football, he was still a force to be reckoned with, especially for anyone that needed to get past him to score. Norm was renowned for his swinging arm in a tackle. Lionel got a tip about this just before his second game against the Diehards. He was sitting with some other players in the Valley when a fan came up and asked him if he was playing against Valleys the next day. When Lionel said he was, the fan told him to get ready to duck.

Lionel did some quick ‘research’ and found out all about Pope’s tackling style. When he got the ball near the try line and Norm came up to try to stop him, Lionel didn’t duck. Instead, he chipped the ball over the surprised full-back’s head, ran around him, picked up the ball and scored. As Lionel was walking back into position, Pope approached Lionel, wanting to know if anyone had told the winger about his tackling style. Lionel grinned and replied in the negative. Not satisfied, Pope continued by saying that not many players would do what Lionel did. Still smiling, Lionel put it down to natural instinct.

The President’s Cup was played for every year at the end of the first round of Brisbane fixtures between the first and second-placed teams. In 1959, those two teams were Wynnum Manly and Norths. Norths was a formidable team and clearly the benchmark of the competition. Seven of their players represented Brisbane in the Bulimba Cup that year (K Anderson, C Churchill, M Cox, J Coyne, W Pearson, W Thomas, L Weier), by far the biggest representation of any club. Captain-coached by Clive Churchill, they were at the beginning of a dynasty, winning six consecutive Brisbane premierships between 1959 and 1964. Despite being hopelessly outgunned on paper, Wynnum Manly caused a huge upset. Through guts and determination, they were not to be denied, downing the favourites by a score of 12-10. The bayside community rejoiced over finally winning their first- ever A Grade silverware.

When Lionel came to Brisbane he got a job working at KR Darling Downs. Later on, he had a chat with Jack Horigan about a career change. Jack worked at the Harbour Marines (later called the Port of Brisbane). Jack asked Lionel if he liked working in the open air. When Lionel enquired what kind of work it was, the reply was shovelling mud for levee banks. Lionel took the job, which included running dredges and pumping material, and worked there for three or four years. He then started skippering launches and became a dredge master – a position he held for 37 years. He enjoyed being on the water all the time and had a varied position description: dredging the Brisbane River, keeping it deep enough for ships; reclaiming land around the Pinkenba area; and skippering tugs that pulled large ships.

In early 1960, Lionel was at the peak of his career, both physically and mentally. He used to undergo strenuous training in the off season. He’d run from where he lived at Wynnum North to the Manly boat harbour and back every morning and every afternoon – about 20 km roadwork in total. Then he would do a lot of sprints as well. In addition to achieving peak fitness, he had also worked hard on his defence. He did not merely want to be an offensive threat. Clive Churchill had given him advice about the best way to tackle and he had practised the technique until he was proficient at it. Clive had preached, ‘They can’t run without legs. Don’t try to take a big man high, otherwise you’ll be flat on your backside’. Lionel always aimed to tackle between the knees and the ankles, and then keep the opponent’s ankles together as he brought him to ground.

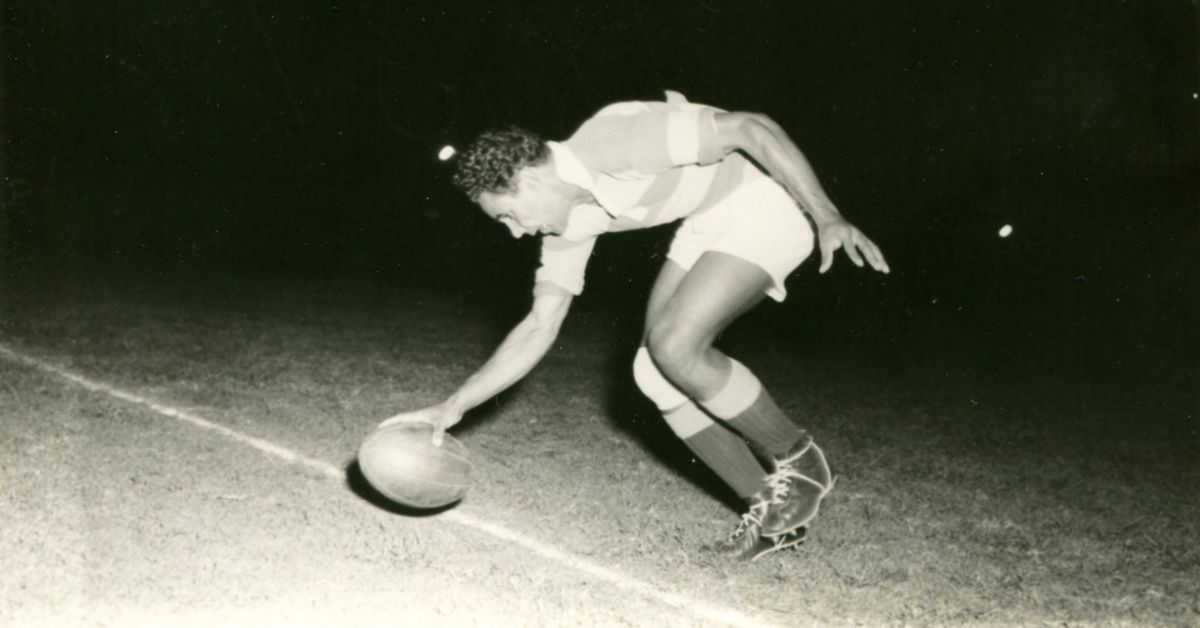

He started off the year in fine style. In a pre-season floodlit night match In March he scored a total of 16 points, including two fine tries and five goals. His form was so impressive his selection for the Queensland trials surprised no-one. The trials were much different to the way teams were picked for NSW. The southerners would pick their side based on one major match – City vs Country. To be picked for Queensland in the 1960s, you needed to play five games in 14 days. First, North Queensland would play Brisbane, Central Queensland took on Toowoomba and Wide Bay went up against Ipswich. Then they would have two City vs Country games and two Queensland vs The Rest matches. This strenuous schedule certainly ensured that any player that represented Queensland was in good physical condition.

When Lionel was first selected to play for Queensland he was a special guest at a function where he received a State blazer and £20, and when he made his debut for Queensland on May 17th at the Sydney Cricket Ground he had a fine match. Unfortunately, the occasion was spoilt somewhat by some unpleasant and unwanted interaction by a spectator. Lionel had just scored a try in the corner. Kevin Lohman had been kicking well early in the game, but had missed the last couple of kicks so the captain, Barry Muir, asked Lionel if he’d like to have a go. Lionel said it would be no trouble. After kicking the goal from about a foot from the touchline, Lionel was walking back to join his teammates. As he did so, he heard a whistling sound. He instinctively ducked and saw a full stubbie on the ground near him. He then heard a racial epithet yelled at him from the hill. Lionel ignored the taunt.

This was not the first nor last time that Lionel would experience racism while playing football. He didn’t see himself as an Indigenous trailblazer, like the African-American baseball player Jackie Robinson who helped break down the ‘colour-barrier’ in Major League Baseball the late 1940s. He decided not to let these kinds of things worry him and just enjoy playing the game he loved. He thought, well if it happened it happened, and that’s the way some people can react at a football game. If he retaliated, he would just be going down to their level. It was the same when a player tried to provoke him on the field. He refused to escalate anything and held no grudges after the game, happy to let things that happened on the field stay on the field.

In his first international match, playing for Brisbane against France on June 13th, the visitors were full of confidence, having just held the powerful Australian team to a draw in the first Test. The game was a very torrid affair, but there were only minor incidents until about 20 minutes into the second half. Brisbane centre Bob Hagan was floored with a big swinging arm to the head by Frenchman Gilbert Benausse. The atmosphere of the game changed immediately, and when the referee, Jack Purtell, awarded the hosts a penalty shortly afterwards, French tempers flared. The referee was pushed and kicked by several French players and touch judge Henry Albert’s flag was snatched away from him. The referee, showing great self-control, did not retaliate. In amongst all this mayhem, Lionel remained calm. He kicked six goals from all angles and was widely credited as being the player most responsible for Brisbane’s remarkable win.

Finally came the day when Lionel reached the goal he had worked so hard to achieve – July 2nd, 1960. On this day, he joyously ran out on to the Brisbane Exhibition Ground in the green and gold of Australia to play against the French in the second Test of the series. The Australian team annihilated the visitors in one of the most comprehensive Test victories ever witnessed, winning 56-6. With Australia having the two fastest wingers in the world in Lionel and Ken Irvine, the Australians just had too much speed for the French to handle. They scored five tries between them and Keith Barnes kicked 10 goals.

Lionel’s two tries were spectacular. The first occurred when Lionel was ‘roaming’ in attack. When Rex Mossop drew three defenders to him, he passed to Lionel who came inside Harry Wells 20 yards out. As he shot through a gap, he used his famous right-foot step to leave three Frenchmen flat-footed and he touched down near the posts. The second try was pure speed. Bobby Bugden, the Australian half-back, ran through the defence and passed to Lionel who raced for the corner, with no Frenchman able to stop him. The crowd roared in approval. Not only was Lionel the first Wynnum Manly player to play for Australia; he was also the first Indigenous player to represent Australia in any major team sport. This remarkable achievement was validated by the fact that he had such a remarkably successful debut.

After another fine effort in the third Test where he thrilled the crowd with several strong runs, Lionel was picked in the 18-man Australian squad for the 1960 World Cup. The tournament was held between September 24th and October 8th in England. Four teams participated: Australia, Great Britain, France and New Zealand. Lionel played in one match – the first of the tournament, against France at Central Park, Wigan. Australia were the ‘home’ team and the referee for the match was Eric Clay. Australia were just able to get up, running out winners 13 to 12. France won the scrums 20 to 14, which meant they had the majority of possession. This negated Australia’s clear speed advantage in their backline. Lionel had limited opportunities, and the French watched him like a hawk, as they had not forgotten his elusiveness in the Tests in Australia. Still, he was able to make some telling breaks and was a constant threat.

After doing so well on the representative stage in 1960, Sydney clubs were more interested than ever in acquiring Lionel’s signature. Two of the keenest clubs were Balmain and Parramatta. However, neither team was willing to pay the transfer-fee set by Wynnum Manly. In 1960, both the NSW League and the QRL decided to adopt a transfer fee system, with the Queensland body’s reasoning being that they wanted to avoid having NSW clubs purloin Queensland’s best players. Lionel wasn’t really worried about playing in Sydney anyway. He had settled in Wynnum and the family was all close. He used to go home and see his parents and all his brothers and sisters on the Tweed every second weekend. He thought he would be a loner if he went to Sydney and that did not appeal to him.

1961 was a momentous year for Brisbane in the Bulimba Cup competition. They had not held the Cup since 1950, and had only won two matches the previous season. However, they were able to find some winning form and were able to go through the competition undefeated. One of the main reasons why was that they were able to build up combinations due to more consistent line-ups. In 1960, 28 players had represented Brisbane, whereas in 1961, only 22 did so. Another reason was that there were three fine additions to the team. Frank Drake had moved from All Whites in Toowoomba to Brisbane Souths and he added a great deal in attack at full-back, scoring five tries that year, including four in one game. Brisbane Wests centre Kevin Lohman had played all four matches for Queensland in 1960 and was in career-best form. Barry Stevens was a forward who had played for Norths in two consecutive Grand Final victories in 1959 and 1960 and brought a winning mentality to the front row.

Lionel scored four tries in the 1961 campaign, all of them against Ipswich. It was against Ipswich at the Northern Ipswich Reserve, with the Cup already won, that Lionel faced the most dangerous racist incident of his career. The thing about racism is that it never changes – the minority can unfortunately affect the majority. Then, as now, a generally boisterous crowd can unequivocally support their local team, but know that there are lines that should not be crossed. It can take just one individual, who doesn’t know or doesn’t care about those lines, who can spoil a match for everyone. And so it happened on May 6th. Lionel had just scored a try when some bloke came up to him from the crowd. The sidelines were very close to the spectators, and as Lionel was walking back onside, the bloke stepped out and punched him in the jaw, while at the same time yelling a racial slur. Lionel played the game out, but his jaw was swollen so he went to stay overnight at the Ipswich hospital.

That was not the only time he spent the night in the Ipswich hospital. On another occasion he received a lot of unwelcome attention from most of the Ipswich team. It is important to note that any ‘black’ elite player in any sport would sometimes receive this kind of attention because he is ‘elite’, rather than because he is ‘black’. The Ipswich players would often read the articles in the Courier-Mail as a kind of scouting report, to see which Brisbane players were playing well and therefore needed to be watched. Before one Brisbane vs Ipswich game, Lionel had gotten a big ‘write-up’. He had been scoring a lot of tries for Wynnum Manly, was having a great season and the journalist said he was a star of the competition. Well, that was like a red flag to a bull. During the game in Ipswich after that article was published, Lionel was tackled into touch. The referee stopped the game and the linesman put up his flag. Play should have ceased – but it didn’t. About 10 Ipswich players joined the ‘tackle’, and the message they were intending to send was well and truly received. Pedro Gallagher even said to Jack Reardon once not to write any complimentary things about him when Brisbane were going to play Ipswich.

Lionel never started an incident, nor got involved in on-field retaliation, so if there was ever going to be a candidate for a player never being sent off in his career, Lionel was it. However, in a match for Wynnum Manly against Brothers at Lang Park, he was sent off for the only time in his career a minute before half-time. Hundreds of people surrounded the referees’ dressing room, shouting insults at whistle-blower Jim Wallace. The quieter people in the crowd were mystified. What had happened? It appeared that Lionel had not done anything to deserve his marching orders. When the hearing was held, the charge was the use of abusive language towards the touch judge. When the judiciary heard the actual wording of what Lionel said, which was, ‘Why don’t you keep your eyes on both teams, linesman?’ the charge was thrown out. However, that was not much comfort to Lionel or the team. For Lionel, there was the injustice of the sending off and for Wynnum Manly, there was the loss of the game because they were a man down.

1962 was the year Lionel became the ‘King of the Bulimba Cup’ (See Special Feature). He already had one Bulimba Cup record – he had scored at least one try in seven consecutive games in 1959-60. In 1962, he added two more records – most points in a game (27) and most points in a season (46). The former was set on April 14th, the first game of the year, against Ipswich at Lang Park. On this occasion he was at his most elusive. He cut the opposition defence to ribbons, scoring five tries and also kicking six goals. Lionel scored (tries and or goals) in every Bulimba Cup game in 1962, and was clearly the best offensive player in the competition that season. Brisbane were able to go through the campaign undefeated for the second year in a row. In 1963, Lionel’s last year playing in the Bulimba Cup, Brisbane only lost one game and thereby were able to secure a hat-trick of titles and retain the Cup. His Bulimba Cup statistics are as follows: 18 games, 23 tries, 39 goals, 147 points.

One incident marred the 1962 Bulimba Cup competition for Lionel – there was another bottle- throwing incident, this time in Toowoomba on July 7th. The match was a close affair, and late in the game the sides were locked at 13 all. Hegarty, Williams and Veivers had scored tries for Brisbane, while Rissman, Dick and Mulhall had done the same for Toowoomba, and both sides had kicked two goals. Lionel broke the tie, getting a three-pointer and kicking the conversion to win the game. After he kicked the goal, he heard a woosh. He turned around and a full stubbie was a couple of feet away from him. As usual, Lionel just kept walking and put what happened out of his mind.

On May 19th, 1962, Queensland played NSW in the second game of the interstate series. For several years Lionel had been considered by many to be the best winger in Queensland and this was still the case. He had played three out of four games in 1961 and the first game of 1962, never having a bad match and always proving a handful for NSW. Although the Maroons lost this game, Lionel played a blinder. He scored the first try of the match, slashing through the defence and pushing off Langlands and then running at top pace to score in the corner. Irvine, the opposing winger whose job it was to mark him, was nowhere near him. He also kicked four fine goals, two of them from acute angles for a total of 11 points. Unbiased observers said he had played all over Irvine. Yet, when the Australian team for the first Test against Great Britain was chosen, the selectors went with Irvine and Michael Cleary, an ex-rugby union international who had played only once for NSW. It can be argued Lionel should have been chosen over both players – but he never played another Test for Australia.

One of the most exciting games of the 1962 representative season was when Brisbane played Great Britain just after the first Test. The visitors had walloped Australia 31-12 and southern critics didn’t give Brisbane much of a chance. England was down 11-14 with 20 seconds left in the game. Brisbane had outplayed the visitors, particularly in the forwards, and deserved to win. Then Eric Ashton, the Great Britain captain, grabbed the ball. The crowd of over 22,000 had been allowed to sit on the grass near the sideline. As Ashton headed for the try line, he actually ran over the sideline and out of play, but the linesman was accidentally impeded by spectators and so did not put up his flag. Ashton’s ‘try’ was allowed to stand. Ashton then converted his own try after full-time to deny the hosts.

1963 was Lionel’s last representative season. While he was chosen for the first Queensland vs NSW match, he did not take any further part in the interstate series. His right knee had been giving him problems since the beginning of the season, which meant that his famous right-foot step was not as dynamic as in the past. Then, when Brisbane played the visiting Kiwis under lights at the Brisbane Exhibition ground in June, he was kicked on his troublesome knee and it became very swollen and sore. He went to see a Brisbane specialist who diagnosed fluid on the knee, and possibly congealed blood. It took Lionel more than three months to completely recover. His fitness suffered a further setback in the Bulimba Cup match in Toowoomba on August 10th. After kicking four goals and helping Brisbane towards victory, he was injured in a heavy tackle near the end of the game. It was first suspected he had fractured his elbow. Luckily, it was only dislocated, but this still meant a significant period of rehabilitation.

Despite the injuries, Lionel played several exceptional games during the season. He scored all of Queensland’s points with two tries and two goals when playing against New Zealand. On July 17th, he scored 19 points (three tries, five goals) in a club game for Wynnum Manly against Brothers and won the Quinn Kelk Holeproof Shirt and the Pearson Brothers award as man-of-the-match. His best try was when he received the ball and moved towards the sideline. The Brothers players thought they had him cornered, but he ran around them, made a burst down the sideline, beat several defenders and side-stepped the full-back to score.

South Africa made its first-ever tour to Australia in 1963. Many people felt the Australian Rugby League made a mistake in judgement by making the tour program too difficult. South Africa was known for its rugby union prowess, but rugby league was in its infancy and a ‘friendlier’ itinerary may have been of more encouragement to the country’s eight-team competition. After getting trounced by Sydney, the visitors put up a much better showing against the Queensland side. Night matches were becoming more popular and this game, like the Brisbane vs New Zealand game, was held under lights at the Exhibition Ground. Seventeen minutes into the second half, Peter Gallagher was sent off by the referee for dissent. Until then it had been a fairly close game, but after the Queensland team were a man short they actually started to play with more intensity and ran out winners, 32-16. Lionel had a great night with the boot, kicking seven goals from eight attempts.

In the latter part of Lionel’s career he was still achieving amazing scoring feats on the field. Against Souths in 1964 at Davies Park he scored a Wynnum Manly club record of six tries in one match. In 1965, as captain-coach, he came up against a young Arthur Beetson. Wynnum Manly were playing Redcliffe on Easter Sunday and Beetson and Kevin Yow Ye were the Redcliffe centres. Artie was running with the ball, and Kevin was backing up. Lionel, playing full-back at the time, knew if he came in to tackle Beetson he would pass off to Kevin. So he quickly decided to run between the two players and call for the ball. Lionel called out, ‘Yes, Art, let me score’, and Artie passed him the ball. Lionel took the ball, ran 60 metres and scored a try. Beetson was not impressed and let him know it.

As a proud one-club player, Lionel played over 150 games for Wynnum Manly. He was on the committee that chose the design for the Seagull emblem in the 1960s. And he is still an integral part of the Wynnum Manly football community today. Loyalty is just one of Lionel’s positive character traits. As a wonderful role-model, the legacy of the ‘King of the Bulimba Cup’ has been to inspire countless Indigenous athletes to strive to not only represent their country in their chosen sport, but to do so with dignity.