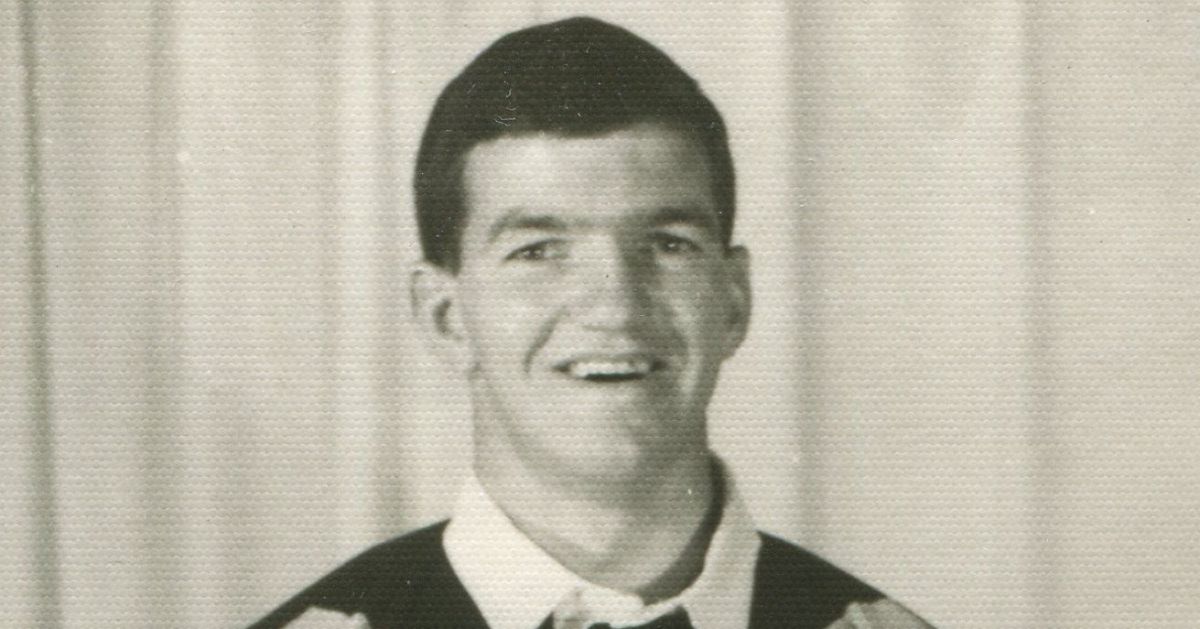

John Gleeson was born in Chinchilla, 260 km from Brisbane, on December 28th, 1938. He was one of nine children (John had three sisters and five brothers). His parents were the biggest influence on John and his siblings. Their family was extremely close, and if one had trouble they all had trouble. This can be evidenced later on, when John gave up a substantial Sydney contract just so he could play with three of his brothers on the same team. His father was a butcher – a hard man, but very fair. All the children wanted to be like Dad. When their father had to go out to the slaughter yard there was a fight among the children about who was going to go with him and help him.

From a young age, John enjoyed several different pastimes. One thing he really enjoyed was music. He would often sit and listen to the wireless, but he also liked to sing, and found that he was quite good at it. Other interests were riding his pony around the town, which many of the children did, and boxing. He had the opportunity to receive some training and get involved in some practice bouts. He thought he was never any good, but he had fun with it. John spent his primary school years studying at St Joseph’s, Chinchilla’s convent school. By his own admission he was not a good student and did not focus much on his studies. The only reason why he went to school was to see his friends and play football.

John started playing rugby league there around the age of seven. Rugby league was a religion in Chinchilla and South-West Queensland and almost every boy played in pick-up games with their schoolmates. When playing with the convent school team he started scoring a few tries and people began commenting that he had some ability. He then got invited to go over to the State school on a Friday afternoon to train and play with their football team. He, along with two other convent boys, were invited to go and play with the State school in their competition. Unfortunately, he got dropped – the school went away to a State carnival and the powers-that-be said it was for State school boys only.

When John was growing up, his favourite player was Ken McCaffery. Ken, a half-back/centre, initially played First Grade with Sydney Easts, but then came to Toowoomba, like so many other players, to play under Duncan Thompson. He captained both Toowoomba and Queensland in 1952, and played 17 times for Queensland and five Tests for Australia. John sometimes got to listen to football games with his family on the wireless at home. He took a special interest when Ken was playing and got very excited whenever he got the ball. John used to hitchhike to Toowoomba to watch Bulimba Cup matches that Ken played in. He could beat three or four blokes just with sheer speed and ability. Any winger that played outside him would turn out to be a great try-scorer. John watched not just as a fan, but as a student of the game.

After he left school he got a job at a car spare parts company in Chinchilla. He joined the Chinchilla Bulldogs as a junior and stayed with the club through under 18s to A Grade, and played either five-eighth or half-back, preferring the latter. Chinchilla played in the Western Downs competition with Jandowae, Miles and Tara. There was also a long tradition of inter-city competition with places such as Roma and Dalby. On one occasion, Chinchilla was playing against Dalby, and the captain-coach of the opposition was international centre Noel Hazzard. The strength of the man is shown in that fact that when young John got caught in a tackle with Noel, with his head between Hazzard’s legs, he blacked out.

For the elite players in the area, the first representative level was to play for the Stockmen in the South-West Queensland team. John played for this team a couple of times as a teenager at half-back, alongside Cunnamulla’s Bobby Banks. John ranks Bobby Banks as the best five-eighth in history – better than Wally Lewis or Darren Lockyer. Everyone feared him when he got the ball in his hands. He was great at creating something. If there was a problem, he could read it – before other players. He made the players that played outside him like Gasnier and Irvine famous for scoring tries because he had great timing when feeding them the ball. On top of all this, he was a genuinely nice guy. He was very down-to-earth, and would talk to the kids on the street and offer them advice.

At the end of 1958, John made a decision to join the Toowoomba Rugby League competition. As no- one in Toowoomba knew who he was, his first step was to try to get noticed in pre-season trial games. In March 1959 he hitch-hiked to Dalby to try to get a game with the Toowoomba Newtown reserves. Unfortunately, he was not able to get an opportunity to play, and so had to return home unsuccessful. The following weekend he went to Toowoomba, hoping that All Whites might give him a chance. He was able to speak with Jack Lee, the president of All Whites, and asked if he could get a run. Jack told him to get changed and get on the field.

He was thrilled to play at half-back, his favoured position, but felt that his performance during the first half of the game left a lot to be desired. He believed that he played so poorly there was no point going back out on to the field for the second half, and so decided to have a shower, get dressed and go home. He was under the shower when he heard a voice yelling at him, ‘What do you think you’re doing? Get out from under that shower, get dressed and go out as five-eighth.’ The voice belonged to B Grade coach Mick Madsen. Mick was generally acknowledged as one of the finest forwards of his era. He was chosen for two Kangaroo tours (1929-30 and 1933-34) and captained Australia, but was probably most famous for his enormous strength. One legendary story tells of how a stranger asked Mick the way to Toowoomba. Mick picked up the plough he was using and pointed out the right road.

All Whites had a ‘problem’ when deciding on their first-choice half-back for the 1959 season, as there were four quality players all vying for the position. Johnny Hodge and Col Howe were already at the club and well established. The two newcomers were John, and Alan Gil. The year before, Alan Gil had been the North Queensland and Queensland Country half-back. Not wanting to lose either player from the starting team, the All Whites ‘brains trust’ decided to have John play five-eighth and move Gil to the centres. The wisdom of this decision is evidenced in the fact that both players ended up representing Australia in their new positions.

John actually preferred the half-back position because he felt he could control things better. However, he understood the decision and set about to ensure he was a success. John knew that as he had little experience at five-eighth, it would be smart to look for ways to improve his game. John started to closely study the playing style of Bobby Banks and tried his best to emulate him. The other key factor in his successful transition from half-back to five-eighth was Duncan Thompson. Thompson preached that a five-eighth is there to serve and look after the backline. You were the link. The five-eighth controlled the direction of the ball. You needed variety – you needed the opposition to be wondering what you were going to do next. If they had a weakness, you’d try to exploit it, try to work at it. He taught John to use his eyes in attack, rather than his brain all the time. If you looked at certain parts of the field, you see the whole field. The most important player on the field was the bloke you were playing beside. He needed to be put in a good position – the key strategy of ‘contract football’.

In John’s opinion, Duncan Thompson was the man that had the greatest influence on Queensland rugby league in the history of the game. Don Furner told John he had come up from Canberra to Toowoomba for only one reason – to be under Duncan Thompson – and john knew of many others who made the same decision. Furner later coached Australia in the 1980s. Thompson instilled belief into his players. He made you believe in yourself and your ability. If you had something that you had to work on, he would take you aside and explain everything to you or get other blokes to come and help you. A great man manager – he had blokes believing they could ‘walk on water’. Toowoomba was called ‘the factory of footballers’ under Duncan Thompson.

When he spoke, no-one dared blink an eyelid. No-one would ever call him Duncan – it was always ‘Mr Thompson’. Everyone had that respect for him. Even blokes his own age called him Mr Thompson. His level of commitment to the game was absolute and he expected nothing less from his players. Henry Morris had come down from Townsville to be under Duncan. He was in the Bulimba Cup team and the team was staying in a boarding house. It was Henry’s turn to do the washing for the week. They were playing the Bulimba Cup final on the Saturday and for the last training session before the game Henry was late. He apologised to Duncan, but the coach told Henry to go home and do the washing – he was too late for Saturday.

The 1959 and 1960 seasons were very successful for John. His club side, All Whites, won two consecutive premierships and Toowoomba won two Bulimba Cups in a row. He had an outstanding Bulimba Cup debut on August 8th, playing against Brisbane at the Athletic Oval in Toowoomba. Although it was in the wet, he played like the ground was dry. John went on several electrifying runs, two of which ended in him scoring tries – no mean feat against a backline that included Clive Churchill and Lionel Morgan. Toowoomba comprehensively defeated their rivals, 41 to 21. His rookie season at All Whites was more than commendable. He played 17 out of 21 games and scored seven tries. By the end of the 1959 season he was starting to be recognised as being in the top echelon of players in the South-East Queensland area.

John could always step and run a bit from an early age. He was never blindingly fast, but over 40 or 50 metres few kids could keep up with him. When he got to Toowoomba he focused on trying to be quick off the mark and then be evasive on the break by using good footwork. He used to train a lot using his feet. Neil Teys, the Toowoomba coach at the time, set up old tyres and lined them up and got his players to run and step through them off a standing start. John was also gaining some renown for his tackling, particularly when taking on big forwards. John practised his timing until he had mastered the art.

One game in particular in 1960 really brought him to the attention of the State selectors. On April 23rd, Toowoomba played Brisbane at Lang Park in the third Bulimba Cup match of the season. Both Toowoomba and Brisbane had beaten Ipswich in the two previous matches of the competition, so this game would set the scene for which team could pick up some early momentum in the championship. John constantly opened up the defence and passed to his outside backs, allowing Toowoomba to gain huge metres in attack. In the try he scored, John fooled the opposition with a change of pace and then raced about 30 yards to score. He was dangerous every time he had the ball, and Brisbane had no answer for him.

The 1960 Toowoomba Clydesdale Bulimba Cup undefeated team reminded everyone of the glory years of the 1924-25 undefeated Galloping Clydesdales (See Special Feature). It was the consistency that they were able to build over the course of the campaign that made the difference. They used the same 13 players all season except for one game when Frank Drake was out injured. It contained four current or future internationals: Frank Drake, Elton Rasmussen Alan Gil and John. Ipswich did come close to them, losing one game by four points and tying the last match of the season. These were the days when all the Bulimba Cup teams would have been able to hold their own against any Sydney club team. All three teams boasted internationals. Brisbane had Ken McCrohon, Lionel Morgan, Bobby Hagan, Mick Veivers and Henry Holloway, while Ipswich included Dud Beattie and Gary Parcell. That Toowoomba was able to go undefeated against such opposition speaks volumes for the class of the side.

The 1960 season with All Whites was the first of many when he played with one or more of his brothers. John and Mick, who was a half-back, each played 15 games out of 17. The team had a fantastic year, with a record of 15-1-1. They lost to Toowoomba Valleys 5-11 and drew with Souths 11-11. In the semi-final they beat Valleys by 10 points, and in the Grand Final they had a comprehensive victory over Newtown 29-5. John scored six tries for his club while brother Mick scored four.

After playing football at a consistently high standard for over two years, John finally got a chance to represent Queensland at five-eighth on June 10th, 1961 at the Sydney Cricket Ground, replacing the man from whom he had learnt so much, Bobby Banks. Unfortunately, Queensland lost by a single point. A broken cheekbone ruled John out of the second interstate game and the New Zealand tour, which was a big disappointment – although he returned to play for Queensland in the final two interstate matches. There was some consolation for John in that because Queensland tied the series by winning these two games they retained the Dr Finn Trophy. John felt very happy that he was able to contribute to Queensland’s success. All the team felt that as they had only lost by a point in one of the games in Sydney, Queensland more than deserved the trophy.

When John left Chinchilla for Toowoomba, his father found a good business opportunity in Toowoomba a short time later – running a butchery in the suburb of Newtown. After six months, the whole family followed him. John was working at a car spare parts shop, but sometimes helped his father. In addition, he was involved in breeding horses and cattle. The other family business was rugby league, and Trevor, who played centre, joined John and Mick at All Whites in 1961. This was a disappointing year for All Whites, losing the preliminary final to Newtown, but they bounced back in 1962 to recapture the premiership for the third time in four years, narrowly beating Toowoomba Valleys 5-4 in the Grand Final. John won his team the title in the last few minutes of the match. He stole the ball from a Valleys forward, ran about 20 yards and scored the winning try. When he was coming back on side, he actually said sorry to his disgruntled opponent.

In 1963 John left Toowoomba to play with Wynnum Manly for one of the highest contracts in Brisbane – nearly £1000. He soon showed the bayside fans his dedication to fitness by often coming to Kitchener Park hours before the other players and doing laps of the oval. When they watched him play, he quickly became a club favourite. He enthralled crowds by the way in which he could step off either foot and seemed to find gaps with ease. His tackling seemed to take a minimum of effort. He played with a smoothness that was rare to see. The year before John came to the club, Wynnum Manly won the wooden spoon in the Brisbane competition, with a 7-14 record. 1963 was a different story, as they were leading on points in the premiership partway through the season. Their record for the year was 11-1- 9, a vast improvement.

On May 26th Wynnum Manly scored 10 tries in a comprehensive win over Easts, 40-13. John scored three tries himself and set up several others with great positioning and passing. On June 2nd, the Wynnum Manly attack was not really firing against Brothers. John got the ball near the halfway, ran around one defender and then with a flash of acceleration beat several of the opposition to score. Until that time Brothers had looked in control. After that the Baysiders noticeably lifted, while Brothers looked rattled. Wynnum Manly ran out winners, 12-10, with most observers of the opinion that John was the difference between the two sides. On July 17, Wynnum Manly’s other star player, Lionel Morgan, scored 19 points against Brothers. John scored a try of his own, with a clever kick-ahead of a loose ball. During the game he got a heavy knock from 95 kg (15 stone) Brothers international forward Peter Gallagher. However, later he picked up Gallagher in a tackle and crashed him into the ground, making him lose the ball. Fans were amazed at the strength of the much smaller Gleeson, and how he tackled with what seemed like a minimum of effort without getting injured. When asked about it, he replied that he depended on the strength in his legs to drive him up through a bigger player when he tackled – it was all in the technique.

With John being a key player in Brisbane’s 1963 Bulimba Cup triumph, and playing well for Queensland, he was chosen as a member of the 1963-64 Kangaroo squad. He had already been in the selectors’ minds, being picked as a reserve for the first Test against New Zealand that year. While John was hospitalised at the beginning of the tour he recovered relatively quickly, and many believed he deserved to be chosen for more than the nine tour games he played (he didn’t play a Test match). To make matters worse, he broke his leg in a game against a provincial French team. Many Queensland observers speculated what may have occurred if Queensland had not been trounced so badly in all four matches in 1963. Both Earl Harrison, the NSW five-eighth, and John made their debuts for their States that year. In the third game of the series John played all over Harrison, beating him with speed several times and bottling him up in defence all match. Yet Harrison played nine Tests for Australia in a six month period, including four on the Kangaroo tour, while John played none. There is no question that Harrison was a good player – but with John in such irresistible form at the time, the fact that Earl was on a winning team seemed to be a significant one.

Despite the lack of playing time, John still enjoyed many memorable moments, on the field and off. He really enjoyed it when Gasnier or Irvine made a break off his lead-up work. It gave him real satisfaction that he had a role in scoring Australian tries. Off the field, he picked up the nickname ‘Dookie’, given to him by Noel Kelly. Noel apparently liked to get into an argument or two, and on occasion, John displayed his pugilistic abilities with his fists, or ‘dukes’. He seemed to have underestimated his boxing skills as a boy. After he got the nickname, everyone started to call him ‘Dookie’ and the name stuck.

The Australians had an opportunity to meet Prince Philip at a Test match. They all had to line up and were told that when he was coming, they were just to hold their hand out – they weren’t to take his hand or squeeze it. He would take your hand and shake it. Naturally, strict protocol was of paramount importance. Standing beside John was Dick ‘Moby’ Thornett. When the prince got to John, a voice said ‘How’s Liz, Phil?’ The manager thought John said it, and looked at him like he was going to shoot him. John blushed. When the prince moved on to Les Johns, a voice asked an even more personal question about the Queen and all hell broke loose. In the aftermath, the managers called all the players in and told them in no uncertain terms that they wanted to know who the culprit was. Moby owned up and said that it was him.

Les Johns was John’s roommate on this tour (and also the 1965 tour to New Zealand and the 1967-68 Kangaroo Tour). The ‘Golden Boy’ was a NSW full-back from Newcastle who played for Canterbury in the Sydney competition. Like John, he was a back-up on the tour – to Ken Thornett. Les represented Australia in 14 Tests between 1963 and 1969. He played with a lot of flair and was an excellent goal-kicker. He, like Frank Drake, suffered from the fact that when it came to national selection, Australia had a glut of top-class full-backs in the 1960s. John and Les became quite close friends, as they naturally got along well together. They had similar personalities: both were genial and decent men who enjoyed a laugh and were popular with teammates.

The non-playing highlight of the tour for John was attending a Beatles concert in London. John went with Les Johns and Earl Harrison. They were wearing their Australian gear, so they were allowed to go around backstage and meet all the members of the Fab Four. The players actually sang a few verses of ‘She Loves You’ with John and Ringo. As a lifelong lover of music, John couldn’t believe his good fortune. When the concert was on, they could hear John and Paul, but when each song stopped, the girls in the crowd screamed so loudly the Australians’ ears were still ringing several hours later.

1964 was the highlight year of John’s career. After being chosen as a reserve for the first Test against the French on June 13th, he finally got to run out in a Test match in the green and gold of Australia – in the second Test on July 4th in Brisbane. The place was packed, but he knew exactly where his mum, dad and girlfriend Dawn (later wife) were in the crowd. He looked up to where they were and they were looking straight at him. The modest side of John came out when the team was announced. ‘Ever since I was a kid playing school football I have dreamt of this moment, but I did not really think it would happen.’ In the second and third tests, John played a major role in both victories. As the main link in the backline, he set up several tries and scored one himself. The French were overwhelmed, and they lost the series 0-3.

Queensland lost all four games in the interstate series for the second year running. The Sydney clubs were getting richer and richer through their profits from the poker machines and the Queensland clubs were getting decimated, with the southerners having no hesitation in cherry-picking the best talent available. Still John was playing at his usual high standards, and still causing headaches for the NSW players. He was rewarded for his consistency when he was awarded the J G Stephenson Trophy for the most serviceable player for Queensland in the interstate series for 1964.

One of the few low-lights on a personal level was when John was sent off for the first time in his career in April, a minute before full-time in a club match for Wynnum Manly against Redcliffe. Many observers and journalists, especially Jack Reardon, questioned the fairness of the decision, considering the inordinate amount of ‘attention’ John had been receiving since the start of the match. According to reports of the game, when Gleeson asked the referee, Col Wright, to look at the targeting he was receiving, he was told that he was a big boy, he should be able to look after himself, and he should stop whinging. On top of this, when he fronted the BRL judiciary committee he was suspended for one game and had to miss a Bulimba Cup match. His previously unblemished record was not even considered, nor was the fact that the normally mild-mannered player was severely provoked numerous times in the game.

By 1965, John’s brother Joe had joined the Toowoomba competition, joining older brothers Trevor and Mick. John, the eldest of the four, had a considerable offer to go and play for Sydney Newtown that year – but the brothers decided they wanted to play on the one team, and so they all signed up for Toowoomba Souths. When the four of them were together off the field it was difficult for strangers to believe they were related. Joe and Trevor were both well over 183 cm (6 feet) tall, whereas John and Mick were only 168 cm (5 ft 6 in). However, when they were on the field they formed an instinctive understanding, and formed a formidable scrum base, with John at five-eighth, Mick at half-back, Joe at lock and Trevor at centre. All three of John’s brothers enjoyed representative careers – playing for Toowoomba in the Bulimba Cup. Mick and Trevor played 10 games each, while Joe played three.

John, Mick and Trevor were members of Toowoomba’s undefeated 1965 Bulimba Cup winning team. Brisbane had won the previous four championships, and many expected them to make it five-in-a-row. However, Toowoomba got off to a great start on April 10th in their first encounter of the year with Brisbane, causing an upset 19-16 away from home. John was the game’s most influential back and Toowoomba front-rower Dennis ‘Monty’ Manteit was the most dominating forward. Dennis came from the same part of the world as John, having been born in Jandowae, 64 km away from John’s home town of Chinchilla. On April 17th in Toowoomba, in John’s second high quality game of the campaign in a row, it was close for most of the match between Toowoomba and Ipswich at the Athletic Oval. John turned in a real captain’s performance, with two swerving runs that led to tries that sealed the match.

At the Bulimba Cup victory celebration dinner, John was asked as captain to make a speech. He said, ‘The Toowoomba team is a great side, and it is an honour to captain the team which won the Bulimba Cup’. He also thanked the officials and sponsor, Queensland Brewery Ltd. Jim Ward, the Toowoomba manager of Queensland Brewery, presented the Cup to John and silver pewters were given to all of the players. Toowoomba Rugby League president Vince Carroll presented the players with their winners’ cheques. Duncan Thompson, who was the special guest speaker, paid tribute to John’s contribution to the team’s success. He said that John was both a tremendous inspiration and example. He also praised John for being a player with a 10-stone (63 kg) body and a 30-stone (190 kg) heart.

John received a tremendous honour when he was asked to captain Queensland against NSW in 1965. He was chosen at half-back – Barry Muir was almost at the end of his stellar representative career. Although Queenslanders were starting to lament the fact that the standard of play of their team was considerably below that of NSW, John was one of the Maroons who could consistently play on the same level as the southerners. The year became even more memorable when he was chosen to go to New Zealand on his second overseas tour. He was only one of three Queenslanders in the touring party. John was picked for five out of the six regional matches, but was not included in either of the two Test teams. The tour had a sour note in that for the second time in his career he received a serious facial injury – a fractured cheekbone and broken jaw. The Kiwis, in a surprise to many, tied the Test series one all.

After a year at Toowoomba Souths, John moved back to Brisbane and joined Brothers in 1966. Norths had won the premiership six of the last seven years and finished on top of the table at the end of the year with 15 wins, 1 draw and 5 losses. Brothers had only one less win and finished second. After losing to Norths in the major semi-final by four points, Brothers just managed to scrape home against Valleys in the preliminary final by a point. So the final was between the two top teams on the premiership ladder. Norths kicked off and John got the ball. As he ran the ball up Norths prop Peter Hall smashed John in the face with his forearm. John’s bottom jaw was suddenly minus six teeth. John told his coach, Brian Davies, that the ambulanceman said that he couldn’t go on again. An angry Davies accused the man of being a Norths supporter. In the 30th minute, he was again violently hit in the head after kicking the ball. There was a scuffle and referee Henry Albert sent off Brothers’ Dennis Manteit and Norths’ Grant Mould – but Mould was lying on the ground unconscious. An angry spectator came on to the field and pushed the referee. Two Brothers players – Arthur Connell and Morrie Pinfold – grabbed the man and pushed him out over the sideline. After the game, which Brothers lost, John had to make an appointment with the dentist to pull the roots of his teeth out. Amazingly, John bore no ill-will towards his opponents.

At the end of 1966, Harry Jeffries named John his ‘Player of the Year’. Jeffries wrote a Rugby League Yearbook in a similar way to E E Christensen, except that Christensen’s book was Sydney-centric, whereas Jeffries’ QRL version was aimed at a Queensland audience. Jeffries commented on John’s remarkable consistency at every level, from club to international matches. He also praised John for always being busy on the field, whose evasive running in attack and consistent cover defence was the key to many victories for the teams he played on.

1967 was the ninth and last year that John played in the Bulimba Cup competition. He had previously been a member of a championship-winning team on five occasions – three times with Toowoomba and twice with Brisbane. On April 15th Brisbane were down by two points with 15 minutes to go and looked like a beaten side. Not for the first time, John was the difference in a close game. A 60-yard run after he accelerated through a gap led to a penalty goal. He then scored a try with a 50-yard burst where he stepped around three defenders. He also set up winger Jeff Denman’s try with an exquisitely timed pass through the narrowest of gaps. Keen observers of the game felt that he was in best-ever form.

On July 1st John was involved in an incident where two players were sent off in the one of the quickest dismissals in Test history – during the second Test with New Zealand. Kiwi prop Robin Orchard knocked John to the ground in the first 90 seconds. Noel Kelly quickly came to his teammate’s aid and made Orchard very aware of his displeasure. Referee Col Pearce sent both of the forwards to the dressing sheds. Fortunately John was not badly hurt. John played in all three Test matches in the series (all won by Australia) against the visitors, scored a try in the first Test, and all but made his selection for the Kangaroo tour certain with polished and consistent performances.

For some time there had been some concern about the number of times John had been hit in the head during games. He had his nose broken 10 times, and had suffered three serious facial injuries (1961 Qld vs NSW, 1965 New Zealand Tour, 1966 Grand Final). There were questions about to what extent John was being deliberately targeted. In attack he was always dangerous because he had the ability to run up to a defence and leave them in two minds about whether he was going to step and run, or pass. Opponents that feared him as an attacking weapon were sometimes not too careful about how they tried to stop this threat. However, no-one had ever systematically targeted him in an ongoing way – that is until the 1967-68 Kangaroo Tour.

In the fifth game of the tour against Wigan on October 13th a knee to the head knocked him out and he spent two days in hospital with severe concussion. In the second Test against Great Britain in London on November 3rd he was the victim of a vicious head tackle and had his nose broken. Against Barrow on November 16th he got smashed in the face again, which caused more damage to his nose – he was only able to continue until half-time. Then finally, there was the third Test in Manchester on December 9th. A British player stiff-armed him in the jaw. He could hear the crack, but showing tremendous courage he stayed on the field. Then in the 22nd minute he was again hit in the head – and now his jaw was broken in several places. Amazingly, he played on for another five minutes, and then he had to come off. The following day he left for Australia with his jaw wired shut and he had to miss the French part of the tour.

Despite all the mishaps on the field, John had a very successful tour from a selection point of view. Unlike on his first Kangaroo tour, he was the first choice five-eighth and played in all three Ashes Tests. He was also selected for 11 games against club teams. He justified the selectors’ faith in him with his best performance of the tour coming in the second Test, just when Australia needed players to step up. The tourists had lost the first Test and then found that four of their first-choice players were unavailable for the second Test due to injury: Billy Smith, Johnny Raper, Dennis Manteit and captain Reg Gasnier. Australia faced a herculean task to square the series. John was asked to play half-back in place of Smith and Peter Gallagher took over the captaincy.

In one of the gutsiest displays ever given by an Australian Test team, Gallagher led the depleted Kangaroos to an upset win, 17-11. Very few gave them any chance of victory. The game was all tied up at two all at half-time, with neither side prepared to give an inch. Despite his injury and having difficulty breathing, John played his heart out, constantly bothering the hosts with swivelling runs and sweetly timed passes. He also was solid as usual in defence, taking on the big British forwards who tried to run over the top of him but failed. In the second half, Australia outscored Great Britain 15 points to 9, scoring three tries to one. With this triumph, the series was level at one Test all, and with a win in the final Test the Kangaroos were the jubilant holders of the Ashes.

Off the field John was rooming with Les Johns for the third time on a tour. Now that they were so familiar with each other, spending time together was hassle-free for both players. Playing more regularly than on the previous tour and being a part of the Test squad meant that John had less time for sightseeing this time. However, he did have one opportunity to indulge his love of music. When he had the opportunity to see Shirley Bassey sing live, he jumped at the chance. Born in Wales, she is renowned for singing three James Bond movie theme songs, most famously ‘Goldfinger’ in 1964. Her other major hit was ‘Big Spender’.

When he arrived back in Brisbane, John was in considerable pain. When he went in to have an operation on his badly injured jaw the surgeons were shocked – he looked like he had been in a car accident. John announced his retirement from football a short time later. In an interview with Neil Groom, he was asked if he thought all the pain from the injuries was worth it. In his reply, John said that football was in his blood and he therefore expected some hard play. He might occasionally question whether it was worth it, but that feeling soon went away when he focused on how much he loved the game. He was also asked if he held any grudges. He answered that he didn’t. When the game was over, everything was forgotten. He felt that this was the only way to play, and if you held grudges you shouldn’t call yourself a footballer.

After retiring, the Courier-Mail conducted a testimonial for John. But a short time later, he decided to come out of retirement – he just couldn’t ignore the empty feeling he had. In a match against Easts in August he had his cheekbone fractured again in questionable circumstances. Once Brothers made the Grand Final, John made a decision that this would definitely be his last game. Brothers finished top of the premiership ladder in 1968 with 16 wins and met Easts in the major semi-final. Brothers won the game, despite being two men down for most of the second half. Kangaroo Dennis Manteit was carried off the field with a badly broken nose and taken to hospital. Hooker Johnny Bourke had to leave the field due to a dislocated shoulder and could not return. John, showing that he had lost none of his attacking flair, was judged by many to be best on ground, despite playing in the unfamiliar centre position. Scoring a scintillating try, he swivelled around four defenders and put the ball down near the posts. He had more penetration than any other player on the field, repeatedly swerving through the defence and keeping the East backs scrambling.

Brothers met Easts again in the Grand Final, and John was particularly happy that he could play the match with his brother Joe. Brothers had a comprehensive win, scoring five tries to none and John had a fairy-tale finish to his career. Brothers lock Wayne Abdy had the match of his life. He was the most dangerous player on either side in attack scoring two tries, and was superb when tackling in defence. Speedy Easts winger Jeff Denman tried hard all match. He came in off his wing position looking for gaps and was beating tacklers, but the Brothers defensive line just had too much experience and class. Joe Gleeson had a very good game, making several important tackles that shut down attacking raids.

After John retired for the second time, he knew he didn’t want to leave the game entirely, so he spent the next several years coaching. In 1969 and 1970 he coached Gympie Brothers and they won their premiership in both years. In his first five seasons of coaching, his teams won four premierships. He learnt most of his coaching strategies from Duncan Thompson. John was tough but fair. The Golden Rule was that if you didn’t train you didn’t play. He expected the players to dress correctly even during training, keep a high standard of fitness, and be proficient with fundamentals such as ball carrying. Most importantly of all to John, he encouraged his players to love the game as much as he did.